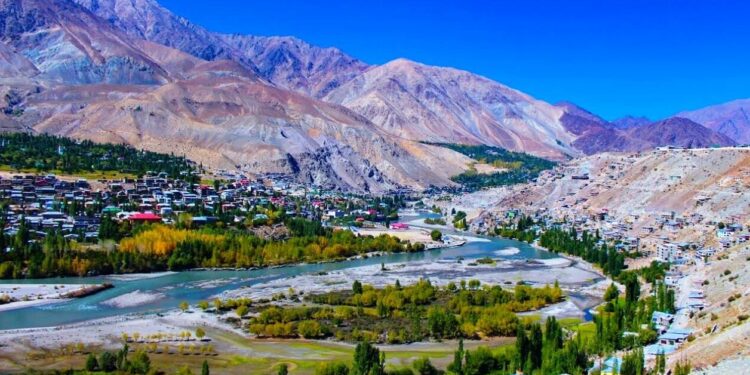

Ladakh: In the breathtaking altitudes of Ladakh, where towering Himalayan peaks dominate the horizon, the fragile ecosystem stands on the brink of an irreversible climate catastrophe. In a bid to save this delicate region, environmental activist Sonam Wangchuk has sparked a movement that has gained huge momentum.

Ladakh’s Long March to New Delhi began on September 1, led by over 100 men and women including retired Indian soldiers like Retired Subedar Stanba of the Ladakh Scouts and local leaders, who set off on a 30-day, 1,000-kilometre trek to India’s capital passing through one of the world’s harshest terrains, icy mountains, crossing altitudes of over 17,000 feet at Taglang La pass.

The region is already experiencing the brunt of climate change, with melting glaciers and erratic weather patterns threatening the livelihoods of those who depend on its fragile environment. Wangchuk’s march has become a symbolic plea to the world, reminding everyone that climate change’s reach extends far beyond remote, mountainous regions. It is a global issue that needs immediate, collective action. The journey, marked by both physical and environmental challenges, has become a powerful statement of resilience, unity and the urgent need for solutions.

Their mission is twofold — to demand constitutional safeguards for Ladakh under the sixth schedule of the Indian constitution and to call global attention to the pressing climate crisis threatening this fragile region.

A group of determined marchers, led by environmentalist Sonam Wangchuk, pause for a photo during their trek through Taglang La pass. Photo: Jigmat Paljor

As the marchers reach New Delhi their message echoes globally, “The impacts of climate change on this ecologically sensitive and geo-strategically vital region have far-reaching implications, not just for India but for South Asia and beyond.”

Ladakh, one of the planet’s most delicate ecosystems nestled in the high Himalayas, is a bellwether for what lies ahead for the entire region. It mirrors the wider Himalayan crisis, where climate change is threatening the lives and livelihoods of millions. This region is warming at twice the global average, putting immense pressure on the glaciers that sustain its people.

The Himalayan glaciers, often called the “Third Pole,” feed the rivers that sustain billions of people across Asia. As these glaciers melt, they are disrupting water cycles, causing floods, and triggering droughts downstream. Ladakh may seem remote but the region’s climate crisis reflects the larger planetary emergency.

In a press conference held at Pong, near the Ladakh-Himachal border at an altitude exceeding 15,000 feet, Wangchuk highlighted the urgent need for sustainable development in the fragile ecosystem of the Himalayas. Wangchuk highlighted the environmental stakes while speaking about the march.

“We are traversing high mountain passes, crossing several challenging terrains, to send a message to the government and the world, The Himalayas are facing the impacts of climate change much faster than anticipated,” he said.

Jigmat Paljor, engineer from IIT Delhi and the coordinator of the march, outlined their progress and upcoming plans. “We’re covering between 25 and 40 kilometres [in] a day, depending on the terrain and the health of our participants, with the goal of reaching Delhi by October 2.”

When asked about economic development, Wangchuk did not mince words. “Economic development must be sustainable for future generations. If we destroy our environment today, we will end up paying far more in the long run,” he said.

Wangchuk emphasised the need for consulting indigenous communities, who have been the stewards of these lands for thousands of years. “Economic development without local input leads to more destruction than growth,” he added.

Wangchuk believes Ladakh’s future lies in sustainable agriculture, adaptive farming, and tourism.

“Ladakh offers unique opportunities. We have herbs and crops that don’t grow anywhere else, and they could be valuable cash crops. Pashmina fiber, for example, is an industry that could thrive, but it’s currently entangled in bureaucratic obstacles,” he explained.

The participants of the crossing a high mountain pass in Ladakh. Photo: Jigmat Paljor

The environmentalist also raised concerns about large-scale industrial projects, which are being developed without consulting local communities. “These projects are capturing valuable pastureland, threatening traditional livelihoods,” he warned.

Wangchuk stressed the importance of preserving the Himalayas for the billions who depend on its resources.

“Around two billion people, including those in North India, China, and Tibet, depend on the glaciers here. If we blindly push for development, the scale of the damage could be catastrophic,” he said.

When questioned about the government’s responsiveness to the march, Wangchuk remained cautiously optimistic.

“Democracy is about people. If people support us, the government and world leaders will have to listen. If necessary, we will fast on October 2 to further our cause,” he declared, alluding to the symbolic importance of the date since Gandhi’s salt march was a catalyst for India’s freedom struggle.

When asked about the widespread reports of industrial interests targeting indigenous tribes across the globe — from the jungles of Chhattisgarh to the Amazon and beyond — and whether his movement plans to collaborate with other global indigenous groups facing similar threats, Wangchuk said, “At the moment, our focus is on the Himalayas. We’re not yet connecting with other indigenous movements worldwide. But it’s not just industries that are to blame — it’s the endless consumer demands from big cities like Paris, Beijing, London, Delhi and New York. These desires drive industrial expansion into vulnerable regions. Our appeal is for people globally to simplify their lives and reduce consumption, which directly impacts fragile ecosystem like ours.”

Climate change and geopolitics collide in Ladakh

The Himalayas hold the largest volume of freshwater outside the polar regions. Ladakh, located in this vast mountain range, has witnessed devastating effects of climate change.

According to research, glaciers in the region are shrinking at an alarming rate. The Chadar Trek, once a popular tourist destination where adventurers would walk on frozen rivers, is now often too risky due to melting ice.

The tragedy is not confined to Ladakh. The entire Himalayan range, from Nepal to Bhutan, is experiencing similar changes. A melting glacier doesn’t just affect local farmers; it impacts the global water cycle, endangering millions who rely on the rivers originating from these mountains. Glacial retreat is accelerating rapidly, leaving behind dry riverbeds and barren land.

Farmers, who once relied on glaciers as a stable source of water, now find themselves facing extreme water shortages. Villages that relied on these natural water reserves are becoming uninhabitable, forcing indigenous people to contemplate becoming “climate refugees”. Glacial melt has also led to unpredictable and deadly flash floods. The 2010 Leh floods, which claimed over 200 lives, serve as a grim reminder of the dangers lurking in this region.

Ladakh, though remote, is not just an ecological treasure. It is at the heart of one of the most geopolitically sensitive regions on earth, lying at the intersection of India, China, and Pakistan. As climate change reshapes the region, it also threatens to heighten geopolitical tensions, with Ladakh caught in the crossfire.

For years, Ladakh has been central to India’s defence strategy, particularly in the face of China’s growing assertiveness. The region shares a long border with China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, and Ladakh’s proximity to Aksai Chin — territory disputed between India and China — makes it a hotspot for military manoeuvring. The 2020 Galwan Valley clashes between India and China underscored Ladakh’s strategic significance in an era where territorial integrity and environmental protection have become intertwined concerns.

Wangchuk’s march reminds India and the world that as climate change accelerates, so too does the vulnerability of regions like Ladakh, where environmental degradation could have severe implications for regional security. The melting of glaciers, for instance, could exacerbate existing water disputes between India, China and Pakistan. As rivers such as the Indus and its tributaries — fed by the glaciers of Ladakh — face depletion, tensions over water resources could rise, with geopolitical consequences that stretch far beyond the region.

Ladakh crisis: A microcosm of earth’s carbon struggle

Beyond Ladakh’s local appeals, Wangchuk delivers a powerful message to the world from Taglang La, one of the world’s highest motorable passes at 17,482 feet. He implores global leaders to cut down on carbon emissions, warning that we have less than five years before climate change spirals out of control.

“We have a climate clock prepared by some of the best scientific minds,” Wangchuk said. “According to this, we have less than five years before things go irreversible and out of control.”

Sonam Wangchuk’s appeal is clear — leaders must recalibrate their carbon emission targets immediately. Photo: Jigmat Paljor

The world’s largest carbon emitters, including India and China, have set targets for carbon neutrality that are far too distant to prevent catastrophic climate outcomes. While countries like Finland have taken decisive action to reduce emissions, others lag behind, choosing economic growth over environmental preservation.

Wangchuk’s appeal is clear — leaders must recalibrate their carbon emission targets immediately, and citizens worldwide must adopt low-carbon lifestyles. “Live simply,” he urged, “So that we in the mountains can simply live.”

Reducing carbon footprint is not just a government responsibility. As individuals, we can make meaningful changes in our daily lives by adopting low-carbon lifestyles, such as reducing energy consumption, cutting waste, and supporting sustainable practices.

The people of Ladakh’s harmonious relationship with nature provides a blueprint for sustainable living for rest of the world. By embracing minimalism and reducing our environmental impact, we can ensure that fragile ecosystems like Ladakh’s are preserved for future generations.

The “Mission LiFE” initiative, launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to promote low-carbon living, is a step in the right direction, but its success hinges on widespread participation.

Wangchuk’s climate march to Delhi also coincides with one of the most devastating natural disasters in the region’s recent history — the 2014 Kashmir floods. The economic loss was staggering — over Rs 5,000 crore, according to ASSOCHAM — and the region’s infrastructure was left crippled.

The devastation wrought by the Kashmir floods offers a grim parallel to the ongoing climate crisis in Ladakh. Both events are stark reminders that the Himalayas are highly vulnerable to climate extremes. What happens in the high Himalayas will not stay in the high Himalayas. The melting glaciers and disrupted ecosystems will eventually have ripple effects far beyond the region, exacerbating water shortages, food insecurity, and migration crises across South Asia. The climate crisis is no longer a distant problem. It is here, and Ladakh is living proof of its devastating effects. And while the impacts are felt locally, the solution requires global cooperation.