In 2017 the student union of one of the most prestigious universities in the UK, ‘The School of Oriental and African Studies’ (SOAS), demanded a drop of “white” philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle and Kant from their curriculum.

Suggesting instead a curriculum replaced with Indian and non-Western philosophers. The demand is inspired by the student union’s educational priority for decolonisation. This was met with scathing responses particularly by philosophers like Roger Scruton, the author of A short History of Modern Philosophy, alleging ignorance on the student’s part.

The demand came even though these three philosophers are some of the most influential men in the Western philosophical tradition. However, given the fact that SOAS is supposed to be an institution that primarily studies South-Asian and African cultures, the request seems fair.

Recently, however, a mixed team of academics and undergraduate students at SOAS produced a “Decolonising Tool-Kit”, renewing the debate on the place of “white”, “male” philosophers in the SOAS curriculum, and by extension in post-colonial times in general.

In this context, I want to argue that despite the exigency of decolonisation and the vital importance of African and South-Asian philosophies, the Platonic Dialogues have continuing relevance and are crucial for the common people to engage with them.

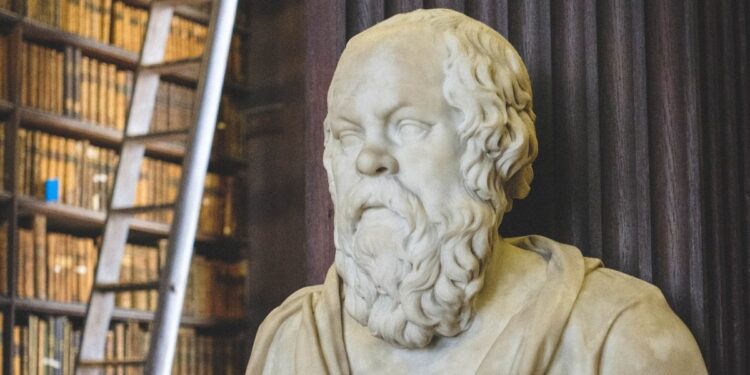

The Platonic Dialogues contain books in a dialogical style, which are supposedly written by Plato, featuring Socrates, who himself left no writings. The dialogues have a subtle sense of humour making them fun to read. But admittedly, the dialogical style makes it hard to follow for some. So why is a body of work written somewhere 2400 years ago still relevant?

Socrates met a tragic end at the age of 70, when he was unjustly accused of impiety and corrupting the youth, tried in an Athenian court, and executed with poison (Hemlock). In the dialogue titled “Crito”, the best friend of Socrates, Crito, visits him in prison and urges him to escape, having bribed the guards. But Socrates has none of it, and decides to have a discussion with his friend on the topic of whether he should indeed escape or not.

The ironic humour of a man debating philosophy at the time of prison break aside, Crito presents several arguments in support of his belief, including a concern for his reputation – what will people think of him if he fails to bust Socrates out of prison?

Socrates replies by asking if an athlete listens to everyone’s advice while training, or if they only listen to their coach. Just as an athlete only listens to their coach, it is prudent for Crito as well, to only listen to the opinion of good men and not of everyone. This reply is pertinent; since, not understanding this distinction has probably landed some in hours of therapy.

The dialogue which describes the trial of Socrates is called “The Apology”. Spoiler alert! He doesn’t apologise for squat. It is in this dialogue that we get a glimpse of Socrates’ famous saying, “All I know is I know nothing.”

Though he never says these exact words anywhere in the Dialogues, Socrates explains that after conversing with politicians who spoke on topics they did not fully understand, he realised that unlike them, he knew nothing because he did not pretend to know what he did not.

He observed a similar tendency in artisans, who, being experts in their crafts, assumed they knew more than they did. Socrates consciously avoided such delusions, making his famous phrase a safeguard against self-deception.

Another dialogue, “The Symposium” is reminiscent since it is literally a conversation among drunk Greeks, including Socrates. The relatability of the scene doesn’t go unnoticed by anyone who has had a drink or two and transformed themselves into a “philosopher”.

The dialogue is a series of speeches on love where we see Socrates admitting that he learnt about love from a woman philosopher named Diotima.

This isn’t surprising since Plato who wrote the Dialogue is arguably the first Western Feminist philosopher. Despite the fact that Plato is known to have made backhanded misogynistic comments, he famously argues that women are just as capable of being philosopher-queens as men. Philosopher-kings/queens are a ruling class of people trained in the sciences as well as philosophy. Patently showing what women were capable.

Plato contends that the qualification of individuals for a particular occupation is not dependent on their differences but on whether those differences are relevant to that profession. For example, to be a carpenter, it is irrelevant if a person has hair on their head or not. Similarly, although there are physiological differences between men and women, these differences are irrelevant to their ability to learn science and philosophy, or govern.

This argument supports the existence of gender-segregated sports in some cases and their irrelevance in others, laying the foundation for recognising injustice when irrelevant differences are used to exclude. It is an answer for anyone who is puzzled as to why if men and women are physiologically unequal deserve equal treatment in some cases.

Answer V: They show the politics of love

“The Symposium” indicates a crude nexus between love and politics. It is asserted that love is important for democracy. Arguing that absolute political systems restrict the liberty of love, sport and philosophy. This connection between love and politics is further explored by feminists who contend that our desires are shaped by class, race, colour, caste, and heteronormativity.

Answer VI: They define “philosophy” in the Greek Tradition

It is further suggested by Socrates that the ‘philia’ (love) in the word philosophy is a sort of brotherly love through which philosophy is born. Showing that philosophy is not isolated ruminations but a communal activity.

To conclude, surely the Platonic Dialogues have been critiqued; but this is not to say that they have become obsolete. Their relevance lies in the perennial discussions they invoke. Furthermore, the Indian political psychologist and social theorist, Ashis Nandy suggests that the Social Sciences and the Humanities do not evolve in a “Darwinian” manner, where older philosophies are critiqued and superseded by newer ones.

This is because new interpretations are found of the text and its utility is not decided by any powerful convention but by those who leverage the text; adducing the marginalisation which Freudian psychoanalysis underwent in the medical sciences, and its subsequent triumphant re-entry into literary studies.

As demonstrated here, Socrates and Plato are yet to lose their relevance and Platonic Dialogues still stand the test time.

Joel Ernest Gonsalves is a Teaching Fellow in Philosophy at KREA University, Andhra Pradesh.